Sadly enough, Ukraine and Crimea have frequently been in the centre of international attention since the Maidan demonstrations and the ensuing (Russian-inspired) disintegration of the Ukrainian State. International Lawyers produced interesting opinions on the legality of Putin's intervention or the Ukrainian government's right not to acknowledge the validity of the referendum. Some legal accounts start the story at Catharine the Great's conquest of Crimea during the Russo-Turkish War of the 1770s. Yet, the fascinating book of Prof. Ferenc Toth (Szombathely Univ.) published in 2011 by Economica, reminds us of the long term struggle for influence between Austria, Russia and the Ottoman Empire, with at its heart control of the Balkans and Ukraine. A combination of Balkan and Ukrainian warfare, recalling both regions' complex history.

A reminder to non-specialist readers of this blog: in the 1730s, the Austrian Habsburgs controlled grosso modo the current states of Austria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Slovenia, Croatia and Bosnia, plus parts of Romania and Poland. Until the end of the 17th century, however, the Ottoman Empire had been at the gates of Vienna. Most of present-day Hungary and the Balkans had been under their control. The Ottoman Empire was not only at odds with the Habsburgs, but with the Russian Empire as well. Czar Peter the Great had expanded Russians domains in the Baltic (to the detriment of Sweden) and in the direction of the Black Sea, where it would inevitably clash with the Turks. In other words, the classical "eastern game" between Austria, Russia and the Turks, traditionally associated with the 19th century and the run-up to World War I, had been in place for quite a time by 1914.

(Europe in 1700; source: Wikimedia Commons. The Austrian Habsburgs' domains go well into the Balkans and present-day Romania and Poland; present-day Ukraine is divided between Poland, Russia, Austria and the Ottomans)

Toth's work is devoted to one specific conflict from 1737 to 1739. Well-known images of the sieges of Vienna (1526, 1683) recall the geopolitical confrontation between the Holy Roman Empire (even under Charles V, almost a synonym for universal monarchy) and the Sultan in Istanbul. Traditionally, historians focus on the battle of Mohacs (1526), where the ruling King of Hungary, Lajos II Jagellon, succumbed and enabled his brother-in-law Ferdinand to bring the latter Kingdom (as well as that of Bohemia) into the Habsburg orbit; on the relief of Vienna and the Imperial reconquest from 1683 to 1699, crowned by the Peace of Karlowitz (26 January 1699); or on Eugene of Savoy's successful campaigns in 1716 an 1717, leading to the fall of Belgrade for the Austrian army. The ensuing Peace of Passarowitz (21 July 1718) was an outright triumph for Emperor Charles VI.

(Emperor Charles VI, Source: Wikimedia Commons)

(Czarina Anna by Caravaque, Source: Wikimedia Commons)

(Sultan Mahmud I "Gazi" (The Warrior); Source: Wikimedia Commons)

However, the situation in 1737 differed fundamentally from that twenty years earlier. Whereas Austria had been at its apex under Eugene of Savoy, the great commander had died in 1736 and the army had performed badly during the War of the Polish Succession (campaigns 1733-1735). Yet, Austria attacked the Ottoman Empire following the opening of hostilities between the latter and the Russians. The explanation is to be found in a text signed ten years before. On 6 August 1726, after the conclusion of the "Ripperda" Treaty (alliance between Spain and Emperor Charles VI), Russia had concluded an alliance with Austria. This combination could easily dominate Central and Eastern Europe. E.g. Prussia quickly abandoned its September 1725 alliance with Britain and France when the threat of an encirclement by the two Emperors became evident. According to one interpretation, the Russians even brought the War of the Polish Succession to an end by transferring troops to the Rhine.

Toth reminds us in his book that the Austro-Russian combination could well have brought the Ottoman Empire to its knees. Especially France was worried that the Ottomans would collapse. The Austro-Russian Alliance had implied not only Russian support for Austria. The opposite was true as well: Czarina Anna of Russia declared war on the Ottoman Empire on 12 April 1736, and urged Austria to provide her with the necessary military assistance. Since Austria controlled Bosnia, Serbia and Temesvar on the basis of Eugene of Savoy's victories in 1717 (crowned by the Treaty of Passarowitz), launching an attack simultaneously would force the Sultan to divide his troops. 54 000 Russians under Münnich (German-born general who beat the French candidate to the Polish throne, Stanislas Leszcynczki) rushed to Crimea. The aim of the Russian expedition was purely punitive: the Tatars operating from the peninsula had to stop their raids into Russian territory. Bahçesarai, their capital, was captured and pillaged. The local Jesuit library was consumed by flames. Yet, the Russians could not remain in Crimea for logistical reasons: they lacked food and water, suffering at the same time from the heath associated with the peninsula. Tatar revenge added to their misery: the destruction of wells and ressources caused the death of 30 000 Russian soldiers. However, Münnich's colleague Lacy did manage to capture Azov (on Ukrainian mainland), bombarding the city from the Black Sea. The explosion of a gun powder arsenal, destroying five mosques, brought the inhabitants to surrender.

The Austrians promised to bring 80 000 men in the field. Both armies could advance towards the south-east of Europe, dividing Moldova and Walachia between them. Austria would aim for Moldova, Greece, Eastern Bulgaria and Macedonia. In January 1737, Austrain ambassador Talman proposed his mediation in Istanbul, but merely to gain time. Austria drew subventions from Rome for a war against infidel and counted on auxiliaries from Saxony, Wolffenbüttel or the Order of Malta. Numerous individual volunteers across Europe enrolled, including an officer from Peru, subject of the King of Spain ! On paper, Charles VI had 120 000 men in Hungary. Formally, the Austrian declaration of war was framed as am ultimatum to the Sultan. Either negotiations brought an agreement between Russia or the Ottomans, by 1 May 1737, or Austria would enter the war on the Russian side. Hostilities focused on Serbia. Yet, the Austrian generals blundered repeatedly. Their armies suffered desertion, and the local Orthodox population did not rebel against the Ottomans, mainly because of the Austrians' intolerant religious policy against non-Catholics. Battle or siege sites sadly recall names from the 1990s: Banja Luka, Belgrade, Nis...

When the Austrian army lost Nis on 16 October 1737, the court in Vienna held its commander, general Doxat, accountable for the débâcle. He was judged by an ad-hoc military tribunal and publicly executed in Belgrade in March 1738. His colleague Seckendorff, who commanded an army by the Rhine during the War of the Polish Succession, was in the centre of Jesuit-led public anger. The Protestant General, who owed his career to the deceased Eugene of Savoy, did not lose his head, but was jailed until the end of Charles VI's reign. Seckendorff had been beseiging Another fortress, Usiza, while the Turks reconquered Nis behind his back!

The Russian army under Lacy could not hold on to Crimea, and had to evacuate the peninsula by September 1737. New attempts in 1738 were stopped by continuous Turkish and Tatar raids, forcing 85 000 Russians to withdraw to Ukraine. Nevertheless, Lacy managed to construct roads and bridges from Crimea to Azov. On the Balkans as well as on the Black Sea's North coasts, the lack of geographical knowledge, bad hygiene, the harsh climate and logistical difficulties brought operations to a standstill.

Königsegg, former ambassador in Madrid in the 1720s, replaced Seckendorff (cf. above, jailed), but to no avail. In August 1738, the Ottomans took the fortress of Adakalé on the Danube and advanced westwards to Belgrade. The situation became threatening, Austria risked losing Belgrade ! Russian aid was not to be expected. In spite of promises to reinforce Transylvania (part of present-day Romania), Czarina Anna saw looming threats in Poland and Sweden, preferring to anticipate a two-front war.

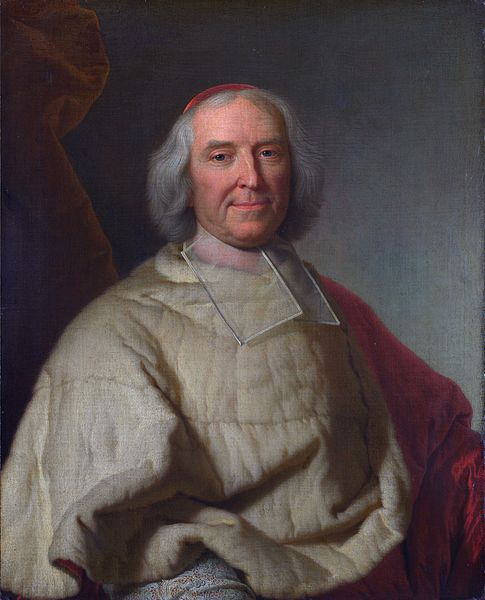

Cardinal Fleury, Louis XV's Prime Minister, feared the rise of Russia. French diplomatic intervention aimed at the swift conclusion of a Treaty of Peace, in order to protect the Ottomans, its privileged commercial partner since the 16th century alliance brokered by Francis I against Charles V. Consequently, France offered to let its diplomats act as mediators between Austria and Russia and the Sultan. The Russians asked for the Maritime Powers' involvement, as they hoped Britain and the Dutch Republic would be less favourable to the Turks.

We should not see this diplomatic game as the equivalent of the web of alliances leading to the outbreak of World War I, where the assassination of Franz Ferdinand put the whole of Europe in arms. Russia would not (yet) participate in an all-out continental war until the Seven Years' War (1756-1763). The main motive for Western involvement was trade. And, of course, prestige. Any power able to impose its mediation on the three eastern Empires would automatically enhance its standing. France had always played this game, hoping the Ottoman diversion would keep the Empire from intervening in the West. Louis XIV pushed it to the most extreme version: while Emperor Leopold I was busy fighting the Turks in Vienna -with the aid of an international coalition- France annexed Strasburg, occupied Luxemburg and bombed cities in the Spanish Netherlands.

In 1739, the campaigns came to a stalemate. The battle of Grocka (22 July 1739) can count as an example: it cost the Austrian army -now under the command of the aged Irish general Wallis- more than 2 000 deaths and of almost 3 000 wounded to obtain a Pyrrhic victory along the Danube. The Ottoman armies employed techniques transferred by the French renegade Bonneval Pasha, and were now using bayonets ! Five days later, the Turks laid siege to Belgrade.

At this point, the court of Saint-Petersburg opted for a quick piece with the Sultan. Fears of Swedish revenge on Russia (to consolidate Peter the Great's conquests, e.g. the current Baltic states), assisted by the French navy, cut Czarina Anna's appetite for further difficult campaigns in Crimea, where Russian cossacks could not stop the Tatars. In spite of general Münnich's taking of Hotin, a fortress in Moldova, Russia tried to bring the conflict to an end. On 19 May 1739, Grand Vizir Yegen Mehmet Pasha, who wished to continue the war until Russia was brought on its knees, was replaced by a less bellicose successor, the Pasha of Vidin. From this moment on, the French ambassador, Marquis Villeneuve, who had been living in Istanbul for ten years, was mandated to mediate between the belligerents.

Charles VI sent Count Neipperg, another of Eugene of Savoy's men, to negotiate a peace deal with the Ottomans. Unfortunately, Neipperg was cut off from communications with the Austrian army. Whereas Wallis had first proposed to surrender Belgrade, he had been summoned to reinforce its garrison. Finally, Wallis even obtained some minor victories, pushing back the Turkish army ! On the ground, the Austrians regained hope. At the negotiating table, however, Neipperg conceded Belgrade to the Pasha of Vidin. Neipperg was incessantly guarded by a company of janissaries, and could not interact with the French delegation. The Turks further intimidated Neipperg by holding interminable military celebrations and interrupting the talks during the Grand Vizir's frequent illnesses. Finally, Neipperg negotiated the cession of Belgrade, with its walls destroyed. The Pasha of Bosnia, replacing the Grand Vizir, brokered the deal. On 1 September 1739, preliminaries of peace were signed between Charles VI and Sultan Mahmut I. Belgrade (art. I) the whole of the province of Serbia (art. III), and the parts of Wallachia occupied by Austria (art. IV) returned to the Ottoman Empire. The alliance between Russia and Austria, however, forbade the conclusion of a separate peace. Consequently, Villeneuve proposed that Russia would keep the city of Azov, destroy its fortifications, and respect the neutrality of the surrounding area. After some commercial discussions on free navigation of the Black Sea (potentially detrimental to French privileges !), the final Peace Treaties were concluded on 19 September 1739.

Finally, a year later (December 1740), Frederick of Prussia invaded Silesia. If the war between Habsburg and the Ottomans had continued, the House of Austria would have been in even greater peril than it actually was... Toth concludes that France came out victorious: the Ottoman Empire had been strengthened. In combination with Prussia's rise, Versailles now disposed of strong "alliances de revers" to block Austrian plans in the West. After the Peace of Belgrade, Franco-Ottoman capitulations were renewed, including potential extensions to the Black Sea.Was Neipperg "a traitor", conceding peace whereas the efforts of the Emperor's military would have allowed for further successes ? Probably not, first in view of his relative isolation but foremost in view of the Austrian's logistical difficulties.

I would warmly recommend reading Ferenc Toth's excellent study on an often forgotten conflict. There is ample material on Eugene of Savoy's glorious taking of Belgrade in 1717, but the less glorious episode twenty years later is all too quickly forgotten. Moreover, for those wishing to see some detail of the pity state Charles VI's army was in at the Emperor's decease and the invasion of Silesia, Toth's book shows many familiar characteristics: quarrelling generals, bad coordination, poor logistical organisation, bad geographical references...

We should not see this diplomatic game as the equivalent of the web of alliances leading to the outbreak of World War I, where the assassination of Franz Ferdinand put the whole of Europe in arms. Russia would not (yet) participate in an all-out continental war until the Seven Years' War (1756-1763). The main motive for Western involvement was trade. And, of course, prestige. Any power able to impose its mediation on the three eastern Empires would automatically enhance its standing. France had always played this game, hoping the Ottoman diversion would keep the Empire from intervening in the West. Louis XIV pushed it to the most extreme version: while Emperor Leopold I was busy fighting the Turks in Vienna -with the aid of an international coalition- France annexed Strasburg, occupied Luxemburg and bombed cities in the Spanish Netherlands.

(Cardinal Fleury by Rigaud, 1728, source: Wikimedia Commons)

In 1739, the campaigns came to a stalemate. The battle of Grocka (22 July 1739) can count as an example: it cost the Austrian army -now under the command of the aged Irish general Wallis- more than 2 000 deaths and of almost 3 000 wounded to obtain a Pyrrhic victory along the Danube. The Ottoman armies employed techniques transferred by the French renegade Bonneval Pasha, and were now using bayonets ! Five days later, the Turks laid siege to Belgrade.

At this point, the court of Saint-Petersburg opted for a quick piece with the Sultan. Fears of Swedish revenge on Russia (to consolidate Peter the Great's conquests, e.g. the current Baltic states), assisted by the French navy, cut Czarina Anna's appetite for further difficult campaigns in Crimea, where Russian cossacks could not stop the Tatars. In spite of general Münnich's taking of Hotin, a fortress in Moldova, Russia tried to bring the conflict to an end. On 19 May 1739, Grand Vizir Yegen Mehmet Pasha, who wished to continue the war until Russia was brought on its knees, was replaced by a less bellicose successor, the Pasha of Vidin. From this moment on, the French ambassador, Marquis Villeneuve, who had been living in Istanbul for ten years, was mandated to mediate between the belligerents.

(Peace Preliminaries, 1 September 1739, Source: Bayrische Staatsbibliothek)

Charles VI sent Count Neipperg, another of Eugene of Savoy's men, to negotiate a peace deal with the Ottomans. Unfortunately, Neipperg was cut off from communications with the Austrian army. Whereas Wallis had first proposed to surrender Belgrade, he had been summoned to reinforce its garrison. Finally, Wallis even obtained some minor victories, pushing back the Turkish army ! On the ground, the Austrians regained hope. At the negotiating table, however, Neipperg conceded Belgrade to the Pasha of Vidin. Neipperg was incessantly guarded by a company of janissaries, and could not interact with the French delegation. The Turks further intimidated Neipperg by holding interminable military celebrations and interrupting the talks during the Grand Vizir's frequent illnesses. Finally, Neipperg negotiated the cession of Belgrade, with its walls destroyed. The Pasha of Bosnia, replacing the Grand Vizir, brokered the deal. On 1 September 1739, preliminaries of peace were signed between Charles VI and Sultan Mahmut I. Belgrade (art. I) the whole of the province of Serbia (art. III), and the parts of Wallachia occupied by Austria (art. IV) returned to the Ottoman Empire. The alliance between Russia and Austria, however, forbade the conclusion of a separate peace. Consequently, Villeneuve proposed that Russia would keep the city of Azov, destroy its fortifications, and respect the neutrality of the surrounding area. After some commercial discussions on free navigation of the Black Sea (potentially detrimental to French privileges !), the final Peace Treaties were concluded on 19 September 1739.

Finally, a year later (December 1740), Frederick of Prussia invaded Silesia. If the war between Habsburg and the Ottomans had continued, the House of Austria would have been in even greater peril than it actually was... Toth concludes that France came out victorious: the Ottoman Empire had been strengthened. In combination with Prussia's rise, Versailles now disposed of strong "alliances de revers" to block Austrian plans in the West. After the Peace of Belgrade, Franco-Ottoman capitulations were renewed, including potential extensions to the Black Sea.Was Neipperg "a traitor", conceding peace whereas the efforts of the Emperor's military would have allowed for further successes ? Probably not, first in view of his relative isolation but foremost in view of the Austrian's logistical difficulties.

I would warmly recommend reading Ferenc Toth's excellent study on an often forgotten conflict. There is ample material on Eugene of Savoy's glorious taking of Belgrade in 1717, but the less glorious episode twenty years later is all too quickly forgotten. Moreover, for those wishing to see some detail of the pity state Charles VI's army was in at the Emperor's decease and the invasion of Silesia, Toth's book shows many familiar characteristics: quarrelling generals, bad coordination, poor logistical organisation, bad geographical references...

.jpg/466px-Louis_Caravaque,_Portrait_of_Empress_Anna_Ioannovna_(1730).jpg)